In 2016, the Central Intelligence Agency completed a special declassification review of the intelligence summary delivered daily to the president from 1961 to 1977. These President’s Daily Briefs (PDBs) provides a candid, granular view of the most important national security issues across two decades and four American presidencies. The PDB is unique in many ways. It was informed by an array of intelligence sources and methods. It was produced on a rigid daily schedule for twenty-five years. It has a relatively consistent format, production process, and mission. Moreover, these PDBs were the subject of a special declassification review which resulted in a relatively consistent set of rules for withholding details considered too sensitive to be made public.

The President’s Daily Brief Project is a data collection effort which builds on what are essentially intelligence artifacts. A team of researchers has extracted text and other graphical material, coded documents, entries, and maps, and built several datasets that help shed light on intelligence, bureaucracy, leaders, and perceptions.

Article: Racial Tropes in the PDB

The first article from this project addresses the way racial tropes affected the way PDB intelligence assessments described foreign policy events.

Carson, Austin, Eric Min, and Maya Van Nuys. “Racial Tropes in the Foreign Policy Bureaucracy: A Computational Text Analysis.” International Organization: 1-35.

Role and Impact

Some suggestion of the promise of the PDB as an object of scholarly inquiry comes from the fame individual PDBs have gained. President George W. Bush infamously received a PDB item titled “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in US” over one month before the 9/11 attacks. The item included the warning that “patterns of suspicious activity in this country consistent with preparations for hijackings or other types of attacks, including recent surveillance of federal buildings in New York.” Former CIA director Robert Gates’s memoir describes the role of the PDB in shaping Ronald Reagan’s understanding of the KAL-007 shoot down in 1983 and George H. W. Bush’s understanding of an attempted coup in the Soviet Union in 1991. Most recently, President Trump is reported to disregard the written PDB in favor of oral presentations with photos, videos, and graphics. David Priess’s excellent book on the history of the PDB, The President’s Book of Secrets, is filled with other examples of its impact.

The PDB’s highly restricted distribution has long generated interest and a mystique among scholars and practitioners. This includes future presidents and vice presidents. John L. Helgerson, a former PDB briefer, describes the eagerness with which Bill Clinton and Al Gore, still awaiting their inauguration, consumed the first PDB, when noting that “our two new customers immediately read every word of that day’s PDB, obviously intrigued to see what it contained.” The intrigue is fueled by the highly tailored — even personal — nature of the PDB, which a former general counsel of the CIA described as “sacrosanct” because it “is advising your client, the president, in the most intimate way.”

The Project

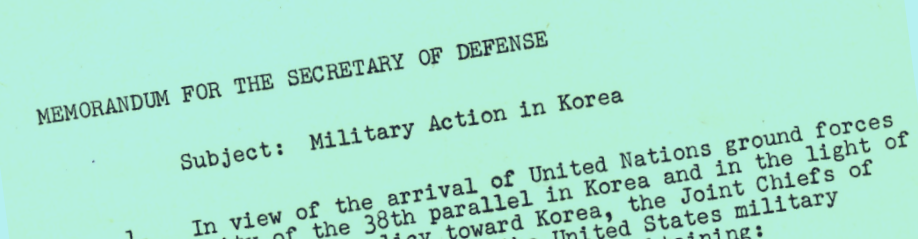

The PDB Project built a research team of undergraduate and graduate student researchers who coded and processed the entire corpus of the declassified collection. The image below of a typical PDB page and item illustrates the kinds of information extracted from a PDB.

The project relies on a combination of software and human coding to characterize various features of each PDB, specific entries, and other features like maps. There are over 4,000 individual briefings in total and over 40,000 individual entries among those. Data from the PDB are the basis of a handful of current article manuscripts and more down the road.

Research Questions

There are many research questions for which this data can be of use. The CIA’s own reports describing their declassification effort give one illustration. Suppose we want to know: Which parts of the world have received the most attention in the president’s daily intelligence summary? Further, we might wonder whether allies or adversaries receive the bulk of intelligence attention, and which individual countries among them? The answer could be interpreted in several ways, but one is that the balance of attention reflects the relative priority the United States attaches to countries and regions. Without access to the PDB, one would have likely have to make inferences from public news reporting or from declassified intelligence reports like National Intelligence Estimates, which are done on an ad hoc basis and infrequently produced.

The image below, from one of the CIA’s own summary, illustrates the potential value in using PDBs to answer this question. Some results are unsurprising. For example, the Soviet Union was reported on in 80% of the PDBs in the sample (1961-1977) and China registers in 57%. But other results are more surprising. Laos appears in 39% of PDBs in this period and the Congo in 21%.

My own PDB Project has explored the following themes:

- Do PDB items display an implicit form of racial bias in how the discuss developments in foreign countries?

- How does the writing style in the PDB change over time?

- What maps are given to the president about which foreign events, and why?

- How do the events covered in the PDB diverge or overlap with the foreign news events covered in the same day’s New York Times?

Support

I have received generous support for the PDB Project from the Social Sciences Division at the University of Chicago, the Summer Institute in Social Research Methods at the University of Chicago, and the College’s CRASSH Scholars Program.